Keynote Lecture with Dr. Asonzeh Ukah

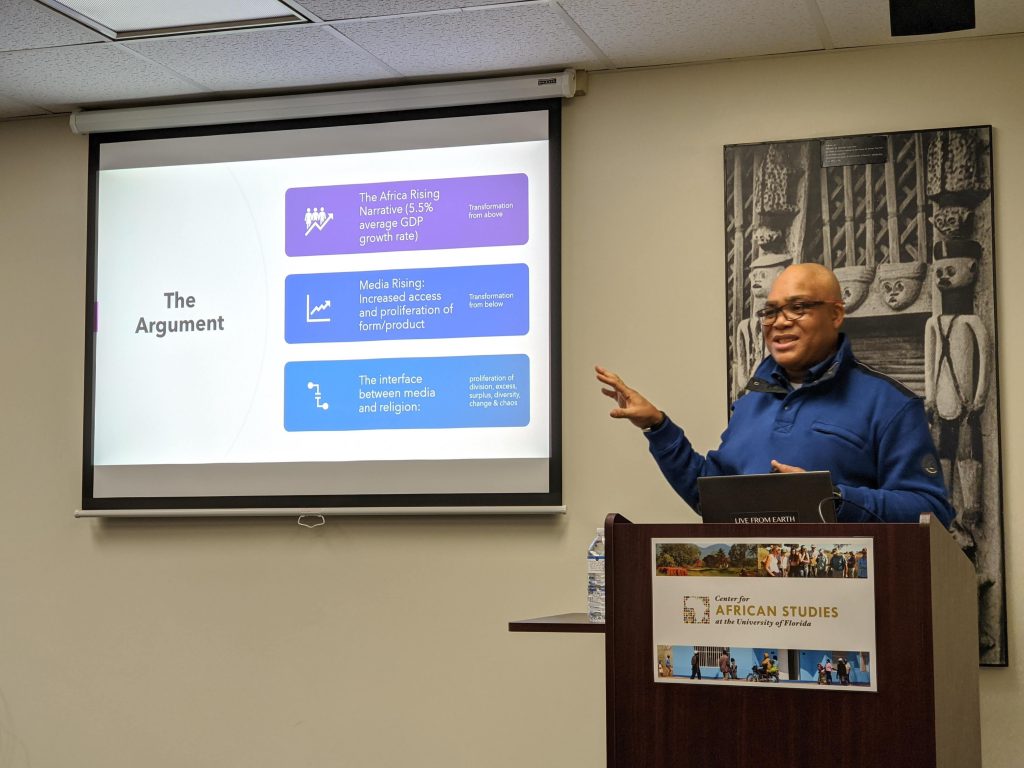

On Thursday, the “Media and ‘Public’ Islam in Africa” Workshop began with a presentation by Asonzeh Ukah (University of Cape Town). His presentation, “From the Excess to the Apocalyptic: Media and the Production of Religious Surplus in Africa,” pointed to the last three decades following the liberalization and deregulation of the media market, arguing that media have lent themselves to a new regime of religious identity never before witnessed. Dr. Ukah stated that the real “Africa Rising” narrative is not how or about Africa and Africans being economically better off during this period but how Africans have mobilized a new array of media forms and platforms to perform and rearticulate both self and the sacred.

On Thursday, the “Media and ‘Public’ Islam in Africa” Workshop began with a presentation by Asonzeh Ukah (University of Cape Town). His presentation, “From the Excess to the Apocalyptic: Media and the Production of Religious Surplus in Africa,” pointed to the last three decades following the liberalization and deregulation of the media market, arguing that media have lent themselves to a new regime of religious identity never before witnessed. Dr. Ukah stated that the real “Africa Rising” narrative is not how or about Africa and Africans being economically better off during this period but how Africans have mobilized a new array of media forms and platforms to perform and rearticulate both self and the sacred.

Using examples from his research in southern Africa, Dr. Ukah described a scene in which a new crop of religious entrepreneurs has emerged and deftly mobilized the media in new ways to re(de)fine the contours of sacred surplus in rapidly shifting sociocultural, economic, and political contexts. He considered the ways that religion has been branded—how feeling is evoked, products are produced, and material objects are used as targets of ritual. This branding links to the concept of religious surplus, where excess, overflow, and spill-overs of ritual symbols, personages, practices, and interpretations resist accommodation within and according to mainstream canons of ownership of religious and social institutions. One example were undergarments being sold in markets with the claim that they could help wearers find a spouse, avoid contracting STIs, and more. These undergarments were affixed with the face of the leader of a religious organization, ‘branded’ as a religious object while also acting as advertising for the group. Dr. Ukah’s lecture went on to discuss the penetration of media on the continent, religious advertising how radio and television is being used as a sacred space, the use of hashtags and social media content in religious participation, and attempts to regulate religious deregulation through counter-advertising and state interventions.

Workshop

Day 2 of the workshop started with welcome remarks by Professor Brenda Chalfin and a short overview of the Luce project “Islam in Global context” by Professor Benjamin F. Soares, the project director. Dr. Musa Ibrahim opened the presentations with a brief introduction on the entanglements between media and ’public’ religion by stressing that it is not possible to understand what ‘public religion’ is or what religion does in public without attending to the processes by which it’s made public, which is by or through media.

Approaching mass media as sources of “culture,” Professor Hatsuki Aishima (National Museum of Ethnology, Japan) talked about how ‘Abd al-Halim Mahmud tactfully employed mass media in his Sufi da‘wa (call, invitation) when public figures in Egypt refrained from disclosing their affiliations to Sufi orders due to negative images attached to Sufism in the 1960s and the 70s. The educated middle-class Sufis enjoyed the comfortable distance between the “master and disciple” created by mass media at a time they were denigrated. Sara Katz (Loyola University, new Orleans) analyzed how, between the 1950s-1970s, ‘Mecca uniform’ was employed for different purposes such as debating politics, exposing corruption, and promoting self-fashioned public images, such as obituary notices in the Nigerian Newsprint. Dr. Frédérick Madore (UF CAS) showed that contrary to general claim, new media does not necessarily instigate change. According to him, the creation of Islamic radio stations in the 2000s made governments in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire to closely monitored Islamic programming, which resulted in a sort of generic Islamic discourse that avoids political debates and confrontations with divergent religious tendencies. Professor Ali Mian (UF Religion Department) provided insights into how the YouTube presence of Pakistani Tablīghī preachers transforms the group’s internal organizational structure as well as their sources of religious authority. Focusing on Mawlānā Ṭāriq Jamīl, he showed that his YouTube activities positioned him as a “public” face of Islam in the Pakistani national imaginary. Lastly, Dr. Musa Ibrahim (UF CAS) engaged with how media practice of representing ‘Islam’ within the popular video culture in northern Nigeria not only symbolizes new forms of convergence between media and Islam but how that triggers contestations about religious practices, styles, and influences authority among different categories of Muslims.

Collectively, the papers addressed the question of how intersections of media and religion in Africa not only make religion much more public, commodified, and personalized set of practices than it has been in the past, but how the realm of both religion and media are themselves transforming and being transformed by each other.

Workshop Recap Guest Written by Dr. Musa Ibrahim

Baraza with Dr. Victoria Bernal

On Friday January 24, Victoria Bernal (University of California – Irvine) gave a Baraza lecture titled, “Cityscapes, Mediascapes, and Diaspora: (Post)colonial Imaginaries of Asmara.” Dr. Bernal is professor of anthropology. Her publications include: “Diaspora and the Afterlife of Violence: Eritrean National Narratives and What Goes Without Saying.” American Anthropologist (2017); Nation as Network: Diaspora, Cyberspace, and Citizenship (2014); “Please Forget Democracy and Justice: Eritrean Politics and the Powers of Humor.” American Ethnologist (2013).

On Friday January 24, Victoria Bernal (University of California – Irvine) gave a Baraza lecture titled, “Cityscapes, Mediascapes, and Diaspora: (Post)colonial Imaginaries of Asmara.” Dr. Bernal is professor of anthropology. Her publications include: “Diaspora and the Afterlife of Violence: Eritrean National Narratives and What Goes Without Saying.” American Anthropologist (2017); Nation as Network: Diaspora, Cyberspace, and Citizenship (2014); “Please Forget Democracy and Justice: Eritrean Politics and the Powers of Humor.” American Ethnologist (2013).

Her lecture examined a series of publications by Western experts on the Eritrean capital city of Asmara in comparison to internet posts by Eritreans. Dr. Bernal considered the imaginings and portrayals of Asmara by both groups in relation to the complex legacies of colonialism and its continuations, the diaspora and internet as spaces of expression, and the ways in which the city serves as a symbolic field. She argues that the internet and media allow Eritreans to represent counter-narratives to mainstream media representations of the city. She detailed the ways in which Asmara has been portrayed in Western media—as a space of aesthetic nostalgia where traces of Italian occupation are preserved and hold high cultural value, connecting Eritrea to a European narrative in which Eritreans are invisible. Meanwhile, Eritreans contest representations of the city—defining and claiming Asmara as a metropolis that is modern, diverse and inclusive, and full of possibilities, illustrated by the sensations, vibes, and mundane experiences of those who identify as Asmarinos.

This workshop was made possible through a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation Initiative on Religion and International Affairs. It was co-sponsored by UF’s Center for African Studies and the Department of Religion.