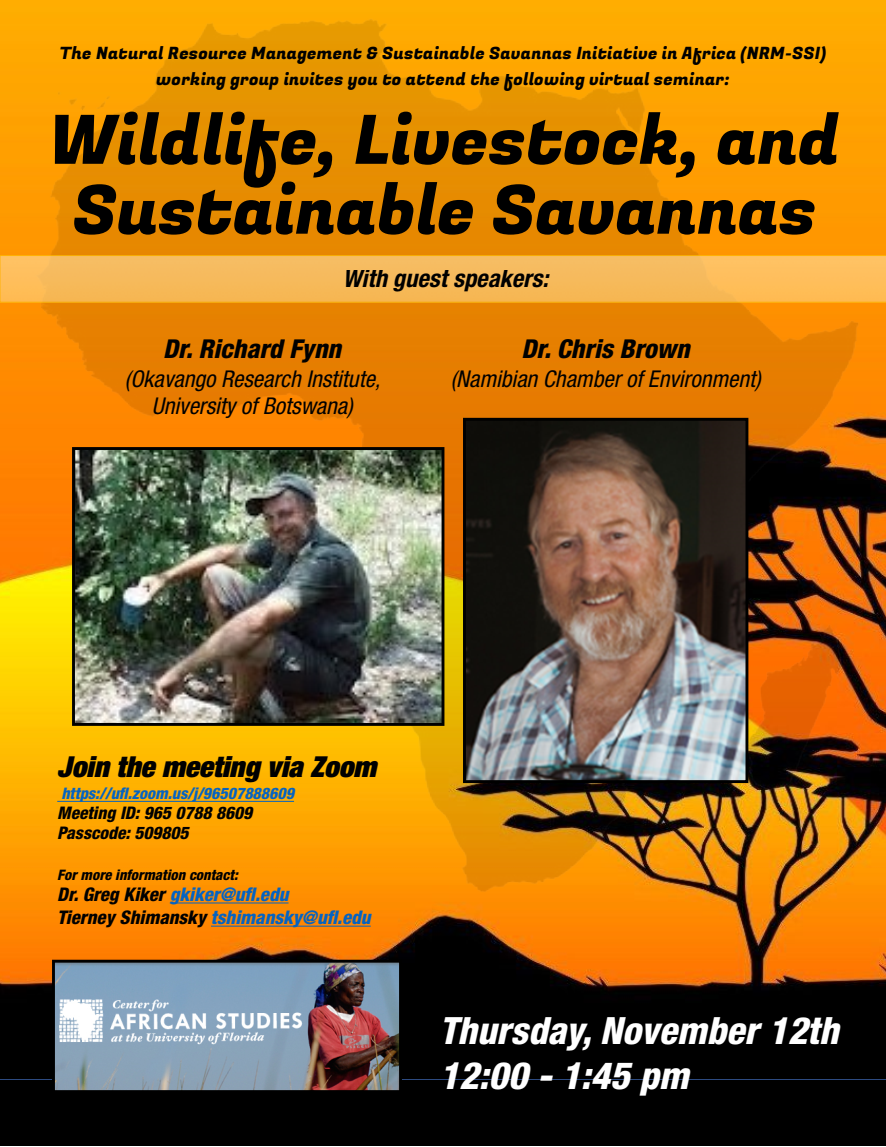

Dr. Richard Flynn from the Akavango Research Institute at the University of Botswana and Dr. Christopher Brown from the Namibian Chamber of Environment presented on “Wildlife, Livestock, and Sustainable Savannas” courtesy of the Natural Resource Management & Sustainable Savannas Initiative in Africa (NRM-SSI) working group.

Dr. Flynn’s presentation argued for “an understanding of the determinants of functional landscapes for resilient social-ecological system[s] in which wildlife and people can co-exist.” He discussed the distribution of functional resource heterogeneity across landscapes. Namely, during the wet season herbivores require high quality forage for proteins and minerals, growth and reproduction, and energy. These food sources are typically digestible, leafy medium height grasses. Most protected areas in Africa are not large enough to encompass both wet and dry areas – which are necessary in order for wildlife to survive and thrive. Because of this, wildlife is forced to rely on foraging in community areas for almost half a year. This has resulted in a stark decline in the wildlife confined to these zones.

The protected areas themselves are designated by the government and not local communities. Due to the lack of control by locals, there has been less of an incentive to promote wildlife. Local communities have lost out and have had to carry the cost of conservation without reaping the benefits. In contrast, external stakeholders like international tourism companies and governments receive most of the benefits and carry little of the costs of conservation. Dr. Flynn states that this creates a “strongly negatively skewed cost-benefit ratio of conversation against local communities…” Which is “a major injustice” and results in communities resisting conservation altogether.

Flynn concluded, “it is becoming increasingly apparent that socially, economically and ecologically sustainable and resilient wildlife landscapes must include livestock as a key livelihood activity for local people.” He ends his presentation by suggesting a Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) approach to overseeing wildlife in Botswana. This framework would allow wildlife and local communities to thrive.

Dr. Brown focused much of his presentation on the devastating effects of climate change on wildlife in Namibia. As CO2 levels continue to rise across the globe, so do temperatures. There are certain hotspots that are experiencing hotter temperatures than initially predicted. One such hotspot is Namibia, Botswana, and the Northern Cape of South Africa. It is estimated that the temperature has risen by 1.5 degrees, approximately .5 more than the rest of the world. This means that by 2025 Namibia will lose 9 million hectares of land for livestock use and by 2065 it will lose another 9 million hectares.

Dr. Brown explains that farmers will be forced into wildlife ranching because small-stock and domestic stock will continue to decline. Moving into wildlife ranching rather than livestock produces more returns per hectare of wildlife. This is because farmers can produce more protein per hectare than from livestock. Wildlife ranching brings in many advantages, for example selling live animals for trophy hunting increases the value of the animal. It can also lead to higher rates of tourism which brings in significantly more revenue. Another way to increase the value of animals would be through wildlife diversification.

Bringing in additional species like water buffalo and rhinos, could create a legitimate market where the value of wildlife would increase and be the competitive form of land use across Africa. One way to do this could be through regional legacy programs. All farmers would be invited to enter into mutually beneficial agreements in which they would all work on the same land to increase tourism, meat production, fish farming, processing facilities and then allow domestic stock to fade out organically.

Dr. Brown concluded his presentation by arguing for a need to “align markets to work for sustainable use of wildlife, conservation of biodiversity and indigenous ecosystem through focused policies and legislation.” By reducing bureaucracy, wildlife could be handled at the local level which would regulate equity and capacity-building services to those who need them.