On Monday, March 12th, Peter Redfield (Professor of Anthropology at UNC-Chapel Hill) gave a provocative presentation titled “Aftermaths: Equipment for Living in a Broken World.” The lecture followed several examples of minimalist humanitarian equipment, or “magic bullets,” and the imaginations surrounding them to interrogate three problem spaces: biopolitical horizons of expectations; the needy human and a mobile milieu; and broken worlds and the scale of the future.

On Monday, March 12th, Peter Redfield (Professor of Anthropology at UNC-Chapel Hill) gave a provocative presentation titled “Aftermaths: Equipment for Living in a Broken World.” The lecture followed several examples of minimalist humanitarian equipment, or “magic bullets,” and the imaginations surrounding them to interrogate three problem spaces: biopolitical horizons of expectations; the needy human and a mobile milieu; and broken worlds and the scale of the future.

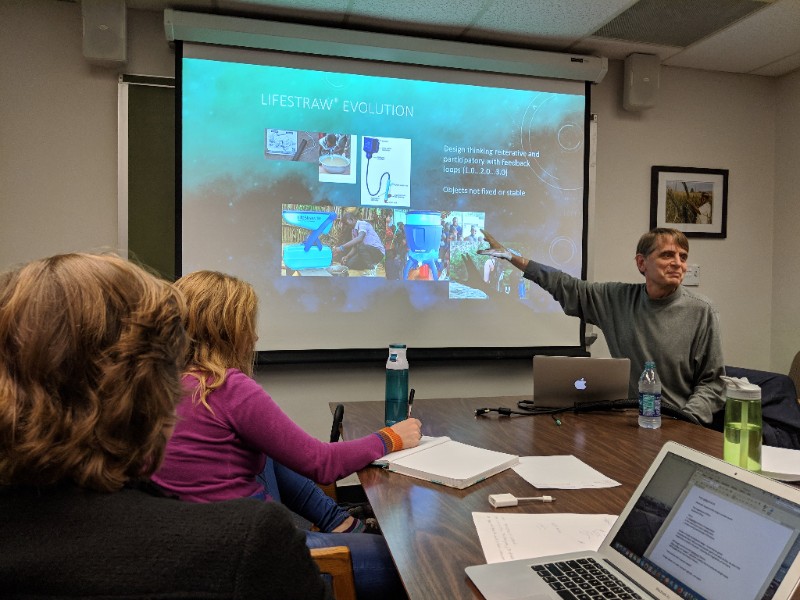

Redfield is not easily seduced by humanitarianism’s transformative visions that aim to change the world. Instead, he asks what it means to intervene in a population and how are biopolitical expectations about life congealed into objects. In the presentation, he used Plumpynut (a ready to use therapeutic food for malnourished children) and the Lifestraw (a gadget that purifies water) to probe the underlying utopian realism of many humanitarian interventions. Because humanitarian kits are built around human needs, Redfield showed how they describe a particular type of life through their provision of materials and imaginaries. He argued that the ‘contained worlds’ of kits (i.e. refugee camps) can be read as mobile milieu of modern norms. He described the Red Cross survival kit to show how human needs constitute more than water, food, shelter, and sanitation/healthcare to include dignity, self-actualization and security.

In more of a provocation than a closing, Redfield ended his presentation by asking (1) are some worlds more broken than others, relative to urban norms, and (2) how do we distribute maintenance and repair as well as innovation? To interrogate this last problem space, Redfield examined the Pee Poo bag, a biodegradable ‘flying toilet.’ This design illustrates how humanitarianism can conflict with popular aspirations of dignity and how popular aspirations may fail to map onto eco-material resources. Redfield points out that these politics of distribution leave many adrift in the moral sea, but who then is in the life boat?