Research Post Written by Megan Cogburn (PhD Candidate, Anthropology)

For the past 8 months I have been in Tanzania completing a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research project. My ethnographic research focuses on maternal health governance and the pregnancy and childbirth care experiences of women in rural communities in the central Dodoma region of Tanzania. I am interested in the everyday maternity experiences of nurses, mothers, and wakunga wa jadi (local birth attendants), and how new global and national policies aimed at increasing facility deliveries intersect with their own care desires and practices. While my project was intended to end late March, I like many others, had to return from the field a bit early due to global public health concerns. Luckily, my project was close to its end and I have prior additional field research seasons to build from for my dissertation project.

For the past 8 months I have been in Tanzania completing a Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research project. My ethnographic research focuses on maternal health governance and the pregnancy and childbirth care experiences of women in rural communities in the central Dodoma region of Tanzania. I am interested in the everyday maternity experiences of nurses, mothers, and wakunga wa jadi (local birth attendants), and how new global and national policies aimed at increasing facility deliveries intersect with their own care desires and practices. While my project was intended to end late March, I like many others, had to return from the field a bit early due to global public health concerns. Luckily, my project was close to its end and I have prior additional field research seasons to build from for my dissertation project.

I first came to Mpwapwa District in January of 2016, through a fellowship with the Transparency for Development Project. I lived in three different villages for 7 months, following community members’ experiences with an intervention aimed at improving maternal health indicators. One of the questions that emerged from this time was what happens to care when it becomes indicator-driven—what does that look like on different levels and in the lives of those giving and receiving care? From this research I wrote an article called, “Home birth fines and health cards in rural Tanzania: on the push for numbers in maternal health,” in press with Social Science & Medicine.

I first came to Mpwapwa District in January of 2016, through a fellowship with the Transparency for Development Project. I lived in three different villages for 7 months, following community members’ experiences with an intervention aimed at improving maternal health indicators. One of the questions that emerged from this time was what happens to care when it becomes indicator-driven—what does that look like on different levels and in the lives of those giving and receiving care? From this research I wrote an article called, “Home birth fines and health cards in rural Tanzania: on the push for numbers in maternal health,” in press with Social Science & Medicine.

My Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Award supported my return to Mpwapwa in July 2019. I had 8 months to ethnographically explore what counts as care, when, why, and to whom, and with what intended and unintended consequences for the lives of women. I chose the village health dispensary— the lowest tier of the Tanzanian biomedical health system — as well as one district-level hospital and maternity waiting home, known locally as Chigonela, as my ethnographic sites. In addition to these facilities, I also sought to follow women’s experiences as they moved through different ‘middle spaces’ of care, which included the homes, churches, and public spaces of respected elders, wakunga wa jadi, and local healers.

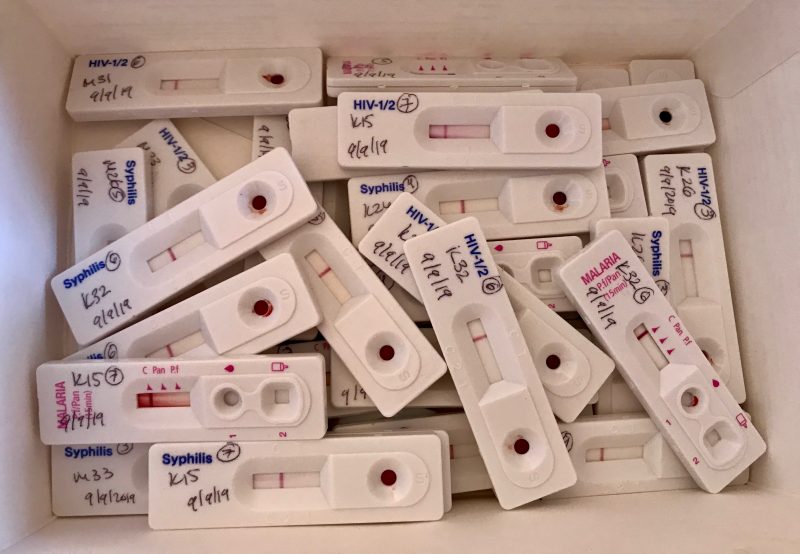

Returning to the same field site 3 years later allowed me to document several changes. Many of which I observed at the health dispensary, where I spent numerous hours helping the nurse register pregnant women, record data, and administer testing. Women are supposed to arrive to the health dispensary early on in their pregnancies—as soon as one feels she is pregnant. They must arrive with their husbands so both can be tested for HIV and STIs, receive a mosquito net, and learn how to prepare for a facility delivery. Due to by-laws banning homebirths, women are not allowed to deliver at home with wakunga wa jadi. Many prefer birth at their local health dispensaries, though fewer and fewer are allowed to do so. This led me to explore the way the dispensary delivery has become the new ‘homebirth’ in interesting ways, leading to novel forms of confessional care at the health facility.

Returning to the same field site 3 years later allowed me to document several changes. Many of which I observed at the health dispensary, where I spent numerous hours helping the nurse register pregnant women, record data, and administer testing. Women are supposed to arrive to the health dispensary early on in their pregnancies—as soon as one feels she is pregnant. They must arrive with their husbands so both can be tested for HIV and STIs, receive a mosquito net, and learn how to prepare for a facility delivery. Due to by-laws banning homebirths, women are not allowed to deliver at home with wakunga wa jadi. Many prefer birth at their local health dispensaries, though fewer and fewer are allowed to do so. This led me to explore the way the dispensary delivery has become the new ‘homebirth’ in interesting ways, leading to novel forms of confessional care at the health facility.

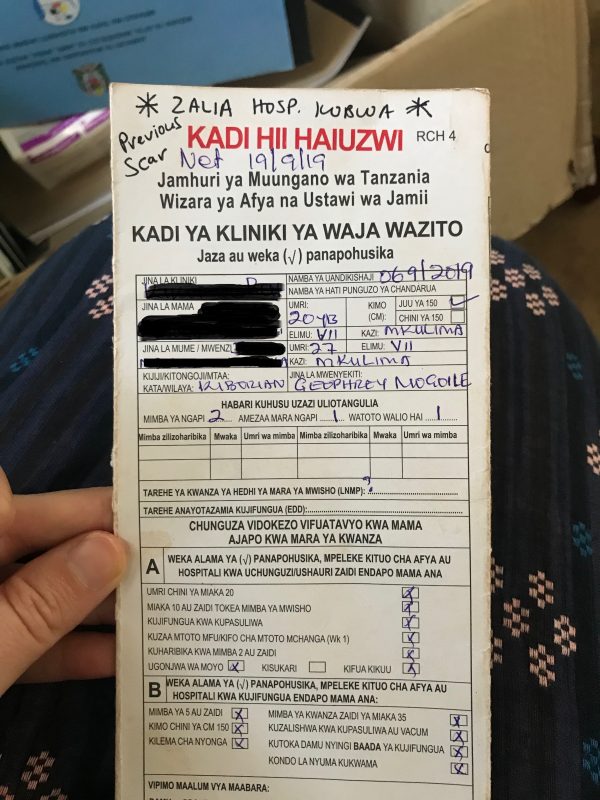

Not all women can access a desired dispensary birth. Commands to go to the district hospital materialize in the stars health workers, or at times, a visiting ethnographer, draw on the top of health cards for all first-time pregnant women, women who have had three or more pregnancies, or previous complications such as caesarean sections. These stars indicate that women must go the maternity waiting home to ensure a hospital delivery. This emphasis on place and temporality —a woman’s early arrival at the hospital—influence much of what counts in the making of ‘good care’ today. However, as women are left to care for themselves once at the maternity waiting home, these same axes of care (time and space) are called into question. The material realities of crowded beds and deteriorating infrastructure pose challenges to daily life at Chigonela, leaving many of its residents to wonder where care is located. The maternity waiting home thus becomes a site shaped by and shaping competing modes of good care and governance. It is a space that seeks to fashion rural, pregnant women into neoliberal, self-caring subjects, at the same time it assumes they cannot care for themselves and are in need of state intervention. The maternity waiting home emerges as a space to rethink traditional forms of governance, (re)imagining the bodies of poor, rural pregnant women, and how best to care.

Not all women can access a desired dispensary birth. Commands to go to the district hospital materialize in the stars health workers, or at times, a visiting ethnographer, draw on the top of health cards for all first-time pregnant women, women who have had three or more pregnancies, or previous complications such as caesarean sections. These stars indicate that women must go the maternity waiting home to ensure a hospital delivery. This emphasis on place and temporality —a woman’s early arrival at the hospital—influence much of what counts in the making of ‘good care’ today. However, as women are left to care for themselves once at the maternity waiting home, these same axes of care (time and space) are called into question. The material realities of crowded beds and deteriorating infrastructure pose challenges to daily life at Chigonela, leaving many of its residents to wonder where care is located. The maternity waiting home thus becomes a site shaped by and shaping competing modes of good care and governance. It is a space that seeks to fashion rural, pregnant women into neoliberal, self-caring subjects, at the same time it assumes they cannot care for themselves and are in need of state intervention. The maternity waiting home emerges as a space to rethink traditional forms of governance, (re)imagining the bodies of poor, rural pregnant women, and how best to care.

One of the things I really enjoyed about my research, and its multi-sited focus, was the ability to be with, different women before, during, and after birth. Some of the women I would see at the maternity waiting home were friends or acquaintances from my time in the villages in 2016. I felt privileged to be able to share in the intimacy and joy that comes in meeting one’s infant for the first time. I was also able to visit many post-partum mothers at home, and conducted focus group discussions with women who had been together at the maternity waiting home and delivered at the hospital.

One of the things I really enjoyed about my research, and its multi-sited focus, was the ability to be with, different women before, during, and after birth. Some of the women I would see at the maternity waiting home were friends or acquaintances from my time in the villages in 2016. I felt privileged to be able to share in the intimacy and joy that comes in meeting one’s infant for the first time. I was also able to visit many post-partum mothers at home, and conducted focus group discussions with women who had been together at the maternity waiting home and delivered at the hospital.

My experience as a researcher in Tanzania was shaped by my own identity as a mother. I am now the mother of two young children. This has added to the complexities of planning and negotiating fieldwork abroad but has also provided my family with amazing memories and new experiences for learning and growth. Some highlights were watching the smiles on my children’s faces when the blue and pink school bus would arrive in the morning and taking long evening hikes together. Before my older son left Mpwapwa, he said that the two things he would miss most are the mountains and stationary shops—the latter of which he frequented more for candy and socializing than pencils or books. Isolating with my children at home now, I am even more grateful for the time and freedom they had in Mpwapwa, and the amazing community who welcomed and sustained us there.

My experience as a researcher in Tanzania was shaped by my own identity as a mother. I am now the mother of two young children. This has added to the complexities of planning and negotiating fieldwork abroad but has also provided my family with amazing memories and new experiences for learning and growth. Some highlights were watching the smiles on my children’s faces when the blue and pink school bus would arrive in the morning and taking long evening hikes together. Before my older son left Mpwapwa, he said that the two things he would miss most are the mountains and stationary shops—the latter of which he frequented more for candy and socializing than pencils or books. Isolating with my children at home now, I am even more grateful for the time and freedom they had in Mpwapwa, and the amazing community who welcomed and sustained us there.

In my unique position as a mother and scholar on maternal health, I have come to value the importance of being open about my experiences with motherhood and scholarship. Final products of research are often missing the mundane, lived experiences of researchers themselves—even though these experiences inherently mold the work we do. Some might think that my position as a mother allows me greater access to the research topics of pregnancy and birth—which it can and does. But, at the end of the day, conducting research as a mother inherently means time away from my children while others provide essential care work so I can carry out the tasks at hand. There are so many mixed emotions that go into these logistics—none of which are unique to me. I think these experiences should be valued more in our writing and reflection as scholars, for the research we do never occurs in a vacuum devoid of our emotions, social ties, and responsibilities. During research, I wonder how our ethnographic care not only reflects our academic training (methods and theoretical underpinnings), but the people we care for in our day to day lives both in and out of the field.

In my unique position as a mother and scholar on maternal health, I have come to value the importance of being open about my experiences with motherhood and scholarship. Final products of research are often missing the mundane, lived experiences of researchers themselves—even though these experiences inherently mold the work we do. Some might think that my position as a mother allows me greater access to the research topics of pregnancy and birth—which it can and does. But, at the end of the day, conducting research as a mother inherently means time away from my children while others provide essential care work so I can carry out the tasks at hand. There are so many mixed emotions that go into these logistics—none of which are unique to me. I think these experiences should be valued more in our writing and reflection as scholars, for the research we do never occurs in a vacuum devoid of our emotions, social ties, and responsibilities. During research, I wonder how our ethnographic care not only reflects our academic training (methods and theoretical underpinnings), but the people we care for in our day to day lives both in and out of the field.

I am so thankful to have had the support of the Center for African Studies and my wonderful advisor and committee members throughout this process. I am also thankful to my friends here at UF, fellow graduate students who have offered me unconditional support and encouragement. One even volunteered her time and resources to help me and my children move to Mpwapwa and lived with us there for a month. The phrase “it takes a village” sounds trite, but collaboration and collaborative practice is key to unmasking powerful hierarchies and making space in the academy for women and caregivers, as many feminist scholars have shown. I believe that collaborative practice can be as simple as a WhatsApp group, such as the one I shared with two of my grad school friends here at UF, both of whom were in Africa conducting research this last year. For over a year, we messaged each other daily, checking in on our research and personal progress, sharing ethnographic vignettes, images, hardships and humor. Our WhatsApp group is not just a testimony to friendship—and perhaps, boredom— but to what ethnography is and might become as we move forward in the 21st century, when, by coming together, we can better care not only for the research process, but for each other.

I am so thankful to have had the support of the Center for African Studies and my wonderful advisor and committee members throughout this process. I am also thankful to my friends here at UF, fellow graduate students who have offered me unconditional support and encouragement. One even volunteered her time and resources to help me and my children move to Mpwapwa and lived with us there for a month. The phrase “it takes a village” sounds trite, but collaboration and collaborative practice is key to unmasking powerful hierarchies and making space in the academy for women and caregivers, as many feminist scholars have shown. I believe that collaborative practice can be as simple as a WhatsApp group, such as the one I shared with two of my grad school friends here at UF, both of whom were in Africa conducting research this last year. For over a year, we messaged each other daily, checking in on our research and personal progress, sharing ethnographic vignettes, images, hardships and humor. Our WhatsApp group is not just a testimony to friendship—and perhaps, boredom— but to what ethnography is and might become as we move forward in the 21st century, when, by coming together, we can better care not only for the research process, but for each other.